Mulcahy Memories |

Fan photos and notes of yesterday. We encourage all Glacier Pilots and Alumni Players to submit photos, films, and videos to this growing collection of Anchorage Glacier Pilots baseball history. Help us preserve the Glacier Pilots colorful past playing baseball in the Last Frontier!

Please use the Contact and Links page or visit our Facebook page to submit. Thank you.

Please use the Contact and Links page or visit our Facebook page to submit. Thank you.

Van Brunt Family

Pat Van Brunt

Patricia "Pat" Van Brunt passed away in her home surrounded by family and friends on May 13, 2013. She was preceded in death by her husband of 56 years, Lefty Van Brunt. Pat was born on February 28 in Atlantic, Iowa and after receiving her nursing degree moved to Seward, Alaska. There she met and married Lefty Van Brunt. "Pat" worked as an E.R. nurse at The Old Providence Hospital, the Community hospital and was an avid "Glacier Pilots" fan and along with Lefty, assisted the team in the office, at the games and helped by providing the players with "goodies" she made from home. During the baseball season, when not at the games, she always had her AM Radio tuned to the pilots' games.

She has requested that no memorial service be held and in lieu of flowers that donations be made to:

"Lefty Van Brunt Memorial Youth Camp" In care of Glacier Pilots

435 W. 10th Avenue, Suite A Anchorage, Alaska 99501

She has requested that no memorial service be held and in lieu of flowers that donations be made to:

"Lefty Van Brunt Memorial Youth Camp" In care of Glacier Pilots

435 W. 10th Avenue, Suite A Anchorage, Alaska 99501

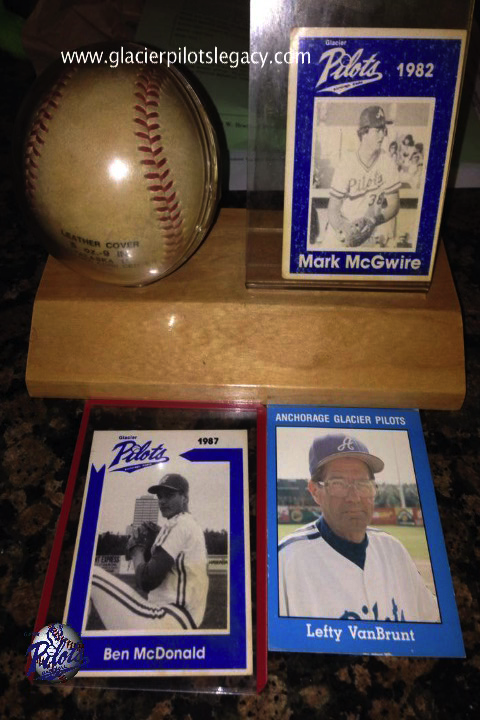

Lefty Van Brunt

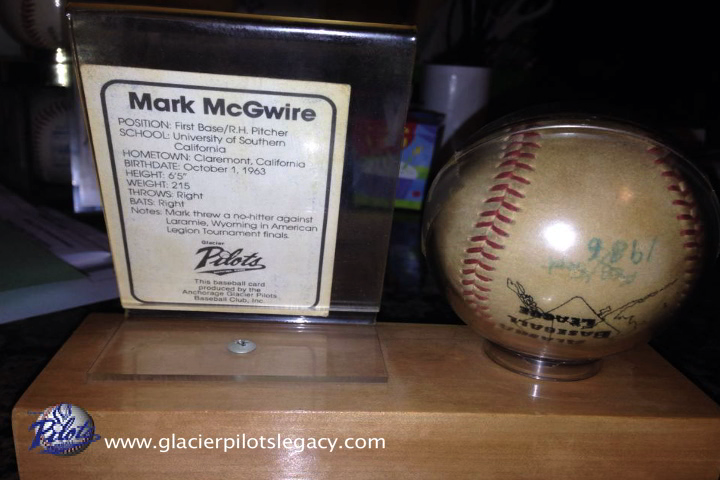

have a future in the game, and others, like Mark McGuire and Randy Johnson, who went on to become superstars.

To many, many people, Lefty was an unrelentingly positive force during the full, glorious bloom of decades worth of Alaska summers, which, though short, are a sublime setting for baseball diamonds. The most important part of Lefty's Legacy, though, to me, and no doubt to many others in my generation, is what he did during the winter. Each winter for decades, Lefty conducted free-and-open baseball skills workshops -- indoors -- to personally help every kid who wanted to get better at baseball and was willing to try. He didn't do it for money, either. Over the course of many years, in leftover warehouse space given to him by SeaLand, Lefty affected the lives of several hundreds, if not thousands, of kids in the Anchorage area. I was a SeaLand warehouse kid, as were most of my friends. Lefty would probably be embarrassed if he heard this, but his influence is one big reason I am who I am today, and I know I'm not alone. Not by a long shot. Because of him, to this day, I can still hit line drives to all fields; I can still make fielding a grounder and making the throw look like one tight, circular motion. All of us warehouse kids were unfortunate enough to love baseball in Alaska, where marginally playable conditions usually never last longer than three months, not including rainouts, and where the peak season itself doesn't last more than five to eight weeks. We knew that baseball activities started for kids in lower latitudes much, much earlier than they did for us, and I suspect we all felt a little cheated about that. Lefty's warehouse sessions were our version of a baseball academy. They were absolutely essential for those of us who loved the game, and we were all lucky to have benefitted. There's no way to overstate how important his work was to us, and there's no way to truly measure his impact on us, both as developing adults and ballplayers. Because of him, I know that passionate dedication to something outside myself is not a mistake. But the warehouse sessions weren't about new-agey baseball mysticism, nor about keeping Alaska's youth from falling into the cycles of violence or substance abuse that saturate their society, nor even to provide them respite from less-than-ideal home environments. I was dealing with my own share of troubles in those days, but I never really felt like I knew Lefty, and I don't think he knew me. But together we knew baseball, and baseball always made things better. |

photos courtesy of Nicole Peterson

|

Lefty probably figured out that his warehouse sessions served important secondary purposes for some of us, but he didn't let on if he did. His workshops weren't therapy sessions. They were first and foremost about baseball. Pure and simple baseball -- much, much purer than the drifts of snow piled outside under the orange-yellow glare of industrial floodlights.

Lefty was already growing old by the time I met him, but the game still looked so easy to him. He reduced baseball excellence to a repeatable set of flicks, snaps, and body alignments. Nice and easy. Now repeat them 20,000 times each. At least.

"Swing DOWN on the ball," he would say over and over again, to kid after kid, as we took cuts at a soft-toss machine inside a netted cage. "Don't break that wrist, keep it level."

"Chopping wood," I can still hear him say.

For almost four years of my adolescence, I spent at least two hours an evening, two or three times a week working with Lefty and lots of other kids from all over town. In that time, I played more catch, took more groundballs, took more batting practice, and made more friends from other leagues than I ever would have been able to otherwise. Kids from every league in Anchorage would show up, and I can't prove it, but I'm sure we got into less trouble on the field because of it.

More than a few of Lefty's warehouse kids went on to have careers in baseball, some in college or university, some even played at a professional level. Baseball never panned out for me as a career, but I knew it wouldn't. I'm certain Lefty himself knew it too. Baseball, for me, would never be more than an extremely fond set of memories and a few sets of motor skills that eventually became decent and permanent, but Lefty taught me with the same attention anyway.

I remember that sometimes, whether we kids were pitching or hitting or fielding, in groups or one-on-one, Lefty would blurt out, "Stop," and we'd freeze. Then he'd ask us, "Where's your balance?" He would reach over with his hand or a fungo bat and push slightly on a shoulder, back or chest. Some of us, usually the newcomers, would start to topple. We never knew when he'd tell us to freeze, so we just assumed he was always watching, waiting for balance to falter.

Lefty and the kind people who let him use the empty spaces around town (for my cohort, a SeaLand warehouse in the heart of Ship Creek's port industrial center), gave me something I will never forget. A big part of it was a chance to play baseball that I wouldn't have had, sure. But more than that, they gave me a measure of responsibility for myself -- and trusted me with it.

That responsibility was apparent to me when, probably my first year as a denizen of the warehouse, say, the winter of 1990-91, the place was full of new cars. For weeks, they sat unprotected, just feet from us slightly above where we played catch. I remember being terrified of making a bad throw, so I concentrated. For everyone's sake. None of us that I remember ever hit one of those cars. We knew if we horsed around and broke something, that would mean our place, Lefty's place, would, well ... Stop.

Where's my balance?

A huge piece of it feels missing right now. Lefty could push me over without even trying.

Lefty was already growing old by the time I met him, but the game still looked so easy to him. He reduced baseball excellence to a repeatable set of flicks, snaps, and body alignments. Nice and easy. Now repeat them 20,000 times each. At least.

"Swing DOWN on the ball," he would say over and over again, to kid after kid, as we took cuts at a soft-toss machine inside a netted cage. "Don't break that wrist, keep it level."

"Chopping wood," I can still hear him say.

For almost four years of my adolescence, I spent at least two hours an evening, two or three times a week working with Lefty and lots of other kids from all over town. In that time, I played more catch, took more groundballs, took more batting practice, and made more friends from other leagues than I ever would have been able to otherwise. Kids from every league in Anchorage would show up, and I can't prove it, but I'm sure we got into less trouble on the field because of it.

More than a few of Lefty's warehouse kids went on to have careers in baseball, some in college or university, some even played at a professional level. Baseball never panned out for me as a career, but I knew it wouldn't. I'm certain Lefty himself knew it too. Baseball, for me, would never be more than an extremely fond set of memories and a few sets of motor skills that eventually became decent and permanent, but Lefty taught me with the same attention anyway.

I remember that sometimes, whether we kids were pitching or hitting or fielding, in groups or one-on-one, Lefty would blurt out, "Stop," and we'd freeze. Then he'd ask us, "Where's your balance?" He would reach over with his hand or a fungo bat and push slightly on a shoulder, back or chest. Some of us, usually the newcomers, would start to topple. We never knew when he'd tell us to freeze, so we just assumed he was always watching, waiting for balance to falter.

Lefty and the kind people who let him use the empty spaces around town (for my cohort, a SeaLand warehouse in the heart of Ship Creek's port industrial center), gave me something I will never forget. A big part of it was a chance to play baseball that I wouldn't have had, sure. But more than that, they gave me a measure of responsibility for myself -- and trusted me with it.

That responsibility was apparent to me when, probably my first year as a denizen of the warehouse, say, the winter of 1990-91, the place was full of new cars. For weeks, they sat unprotected, just feet from us slightly above where we played catch. I remember being terrified of making a bad throw, so I concentrated. For everyone's sake. None of us that I remember ever hit one of those cars. We knew if we horsed around and broke something, that would mean our place, Lefty's place, would, well ... Stop.

Where's my balance?

A huge piece of it feels missing right now. Lefty could push me over without even trying.